By LC Publisher: APCNews CALGARY,

Published onPage last updated on

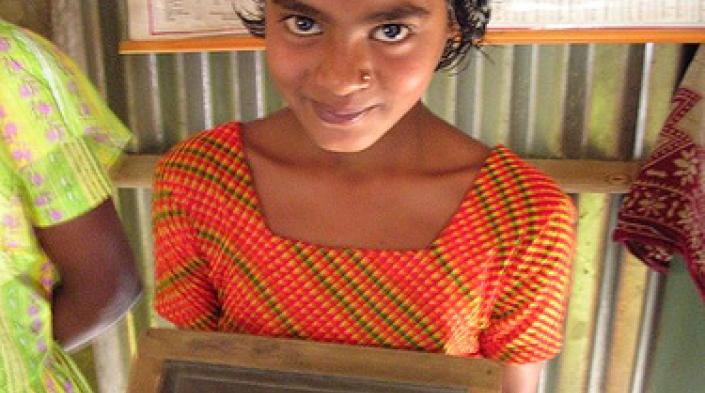

Bangladeshi schoolchildren, just like most children worldwide, want to get connected. In a country that is largely comprised of rural populations that survive on subsistence farming, internet access and computer skills aren’t necessarily always high on the priority list in schools and small communities. Yet poor Bangladeshis realise that that being up to speed with technology is an important part of pulling themselves out of poverty. In a country where only one out of every two men and only three women out of every hundred can read, access to information (via ICTs especially) can mean access to job opportunities or new farming techniques.

D.Net, a non-profit organisation that focuses on technology for economic development saw the need for content in Bangla to cater to rural people’s information needs. In an effort to help underprivileged rural youth build their computer skills, they developed a programme to teach them how to use computers – the Computer Literacy Programme (CLP). By June 2009 D.Net was operating 107 computer literacy centres in 39 districts across the country, and a total of 18,556 students had successfully completed the CLP course. To improve the training, D.Net wanted to learn more about what types of information the students, their parents and teachers need and how they view technology. Using the APC’s Gender Evaluation Methodology to conduct the study, they uncovered some views about technology that surprised them and which they believe would not have surfaced if the study had not included a gender focus.

Against cultural norms – access for girls is a challenge

The GEM study found that cultural factors play a bigger role in whether or not a girl attended the training than lack of money or resources. Co-founder of D.Net and CLP lead Mahmud Hasan explains that girls are often denied the chance to even participate in any sort of computer training because it is considered socially inappropriate.

“Computer classes in schools are extra-curricular and usually held before or after regular classes. The biggest problem is that girls have to stay after school when it is dark out. So despite their interest, they are not allowed to attend the course,” he says.

But girls are not left in the dark for this reason alone, it seems the entire community often favours computer access for boys over girls. Mahmud explains that not only do fathers encourage their sons over their daughters, but teachers also generally push for boys to access the internet over girls – and this mentality can be found through the community at large.

“If a boy is attending a computer course, community members encourage him to continue, but opinions are mixed where girls are concerned. Elders and community members ask her why she wants to complicate her life, especially when she already spends so much time at school and has so many chores at home,” explains Mahmud.

Even D.Net’s sponsors seem to favour boys. One of D.NET’s core fund-raising strategies is to seek funds from Bangladeshis living overseas. These migrants generally sponsor a school in the villages where they were born and brought up. “We noticed that few girls schools got sponsored, unless the particular donor was female,” says Mahmud.

The GEM evaluation encouraged Mahmud’s team to reconsider their fund-raising policy which asked sponsors to select the schools they wished to support. Instead, backed by the GEM results, D.Net encouraged their sponsors to give D.Net the flexibility to choose the schools most in need. As a consequence, now D.Net equally favours boys and girls schools and of the almost 20,000 students who had completed their training in June 2009 52% were girls.

ICTs for domestic income generation

The GEM study revealed that girls saw the utility of ICTs for domestic income generation through handicrafts and textiles by accessing designs from CDs and the internet – something none of the boys mentioned.

“When asked about the benefits to taking a computer class, responses from boys and girls were different,” outlines Mahmud. “Boys referred to getting jobs, doing computer business, setting up cyber cafés or telecentres whereas girls saw how to apply computers for creating new income generation opportunities from the home. The girls interviewed told us that they could get various types of designs from the computer, which they used in the production of handicrafts, like carpet-making.”

GEM unearths the invisible

As a methodology developed to identify gender gaps in technology projects, GEM helps measure the not-so-tangible qualitative issues related to cultural beliefs, subtle (and not so subtle) gender differences and other factors that may not be visible or concrete but can have a huge impact on the success or failure of a project.

Initially somewhat skeptical about the value of using a gender-focused methodology, D.Net has now come to realise that technology is socially constructed, meaning that culture and social norms have a direct impact on gender roles and therefore affects to what extent it is socially acceptable and appropriate for boys and girls to access ICTs (for instance in Bangladesh this can be expressed through the willingness of a parent to send their girl children as opposed to their boy children to computer classes). While D.Net staff realises that a rural ICT for development project cannot automatically address gender gaps related to access, GEM gives them the tools they need to consciously plan for and ensure that women and girls are given equal and accessible opportunities throughout the project’s life-cycle.

Applying the GEM “gender lens” (a gender analytical perspective) during planning, data collection and analysis D.Net was able to build breakthrough opportunities for girls into the project in direct consultation with mothers, female teachers and the girls themselves. D.Net intends to expand the CLP project to 1,000 schools by the year 2011 and will place special emphasis on girls schools.

D.Net: Leading the GEM way in Bangladesh

Now convinced that to change social conditions in Bangladesh women and girls unequal status and opportunities need to be addressed, D.Net recently (13-14 February, 2010) organised the first ever national GEM training with ten participating organisations including development groups such as Action Aid Bangladesh.

“The objective was to introduce GEM to development practitioners in Bangladesh,” Mahmud states. “The enthusiasm among participants showed us the possibility of engaging them on a sustained basis.” He explains that it was encouraging to see that people who underwent the training felt committed to incorporating GEM into their own monitoring and evaluation strategies, and that they wanted more in-depth training, as well as additional support to introduce the methodology to their partners. “This will create an opportunity to bring gender equality to tens and hopefully even hundreds of initiatives in Bangladesh,” says Mahmud.

Photo: “Mark Knobil via Flickr” (http://www.flickr.com/photos/knobil/)