Publicado el

Actualizado por última vez en

Internet governance (IG) was bright and shiny once. New technologies and new ways of governing technologies suggested that there might be ways of changing how public policy gets made – not least by bringing more diversity into decision-making through multistakeholder participation. But has the shine come off? Is it now time for a reboot?

That’s the case put in a paper by Kieran McCarthy, published by the Tony Blair Institute. Some opening thoughts, a summary of McCarthy’s paper, and some issues that arise from his suggestions.

The internet governance ecosystem

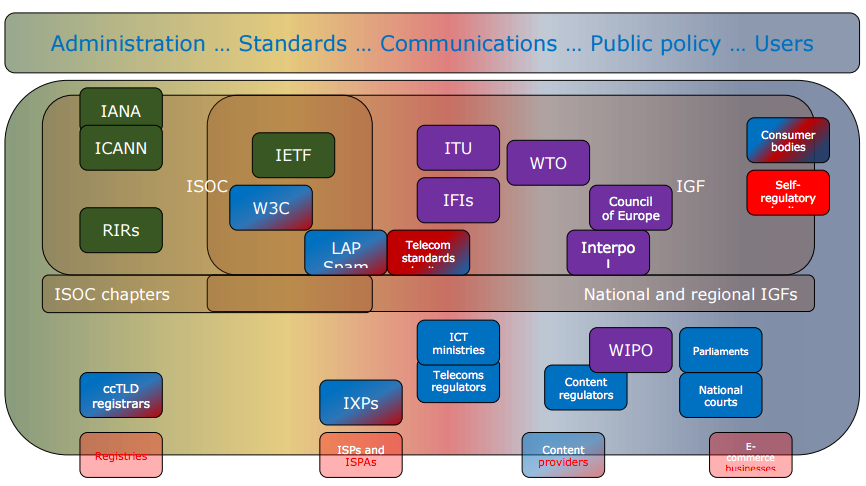

Twenty years ago, at the World Summit on the Information Society, governments woke up to the way the internet had developed outside normal governance arrangements. A bunch of technocratic bodies had led the design and deployment of a new communications system that had seemed small but turned out to be big and getting bigger. Those technocratic bodies included, for example, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

They have been joined since then by other kinds of governance around the internet: by powerful corporations setting rules for citizens’ engagement with them and their services; by international standards concerned with impacts like cybersecurity that have been agreed by diverse entities; by national regulations concerned with competition, content and citizens’ rights or (in some countries) their suppression.

But the technocratic bodies have remained central to the way the internet works and develops. McCarthy argues that the way they’ve done so’s led to a culture of "entrenchment that favours the status quo, excludes fresh perspectives and limits the very dynamism that made the internet possible in the first place.”

A context

I’ve argued often in this blog that the way the internet was governed in its early days – an upstart technology with limited applications and even more limited impact, dominated by one high-powered economy – was inherently unlikely to suit what it’s become – the world’s leading communications medium and a powerful, sometimes determining, force across all aspects of society and economy, in countries of all kinds, both powerful and vulnerable.

That disjunction ought not to be controversial. The ways that things are governed should be based on circumstances now and those anticipated for the future, not on the way things were (though past experience is obviously influential). The internet has changed many aspects of how other things are governed (think of e-commerce, cybersecurity, the datafication of our lives), and required changes in the governance of all of them. It would be odd if its own governance did not also require adjustment to its evolution.

There’s nothing specific to the internet in this. There’s a tension in most evolving social/economic/political contexts between the way things were and the way that they may need to be today and in the future. Sometimes this is characterised as a tension between ‘conservative’ and ‘progressive’ views; sometimes as a choice between ‘principle’ and ‘pragmatism’. Vested interests – for either status quo or change – play a big part.

The grounds for changing institutional dynamics, though, are evident, especially in something as fast moving as the internet. Technology makes new things possible – both opportunities and risks. Outcomes – both positive, worth replication; and negative, worth mitigation – become clear, in areas that are both technical (such as cybersecurity) and social (such as mis/disinformation). Circumstances change – geopolitical tensions, for example, or impacts on climate change. And so, in time, do the values and principles that people expect to be reflected in their governance (think, for instance, of the impact of feminism or changing attitudes towards social equality).

All governance norms are affected by such changes, requiring reinterpretation or revision if they are to stay appropriate. This tension’s often difficult to resolve and can be polarising. Look at the US constitution, for example: a document written in an age of muskets that is struggling to apply eighteenth century norms to today’s assault rifles.

“Neutrality”

So what’s McCarthy’s argument?

First, he notes that the core governance bodies on the internet are concerned with technical issues rather than their outcomes. This has led them to focus on the stability of the internet itself rather than the ‘flexibility and innovation’ that it can promote. Some see this technical neutrality as virtue, but the internet’s development and growing significance pose obvious challenges and require changes in other areas of governance (such as environment and rights).

I agree this is a major problem. For governments, businesses and citizens, what matters most is what the internet does to their societies, economies and cultures – what works best for those and what might harm them, not what seems best for the technology that has those impacts and the technologists responsible for them.

Governments, businesses and citizens want to make use of the internet in their own interests (which aren’t always benign), but are also fearful of what might go wrong. Hence, tensions over regulation and the gap between governments’ (and citizens’) precautionary principles and internet technologists’ desire for permissionless innovation.

The problems that McCarthy sees

McCarthy sees four problems arising from the way the core technical bodies are working now.

First, lack of coordination. They keep within their specific responsibilities – the domain name system in ICANN, for example – and interact too little with each other, let alone with outside bodies whose roles are going to be affected by the decisions that they take.

Second, lack of strategic direction. Their plans are insular, focused on resolving problems of the past rather than anticipating issues for the future. Their founders have remained too influential.

Third, weak internal processes. Old ways of doing things are seen as virtuous when newer ways, more suited to today’s technologies, circumstances and diversity, would be more productive and appropriate. There’s little external accountability.

And fourth, weak participation. While IG bodies may be open to anyone in theory, there are high barriers to participation. Their focus on technical expertise discourages consideration of non-technical implications and the involvement of those whose expertise is non-technical. The high cost of participation favours those from larger companies and richer countries.

And so?

McCarthy summarises the implications of all this, quite harshly, thus: “The internet is suffering from a case of founder's syndrome: resistance to change, paranoia, a lack of strategic direction and accountability, the sidelining of people brought in to fix problems, and a failure to plan for succession.”

“[A]s the internet continues to evolve in rapid and unexpected directions,” he adds, “its governance organisations need to follow suit.” While this may sound obvious, the implications for IG institutions are not simple. They involve untangling long-established ways of doing things that are still cherished by many actors, not least because they were once radical innovations in which they played a part.

It is, of course, much easier to create new governance institutions for new technologies (such as the W3C) than to adapt those that are long-established for new times. Change is possible (as ICANN has shown) but it takes time and does not necessarily address the whole gamut of issues (ICANN’s work may be transparent to habitué(e)s, but it’s opaque to the vast majority who aren’t).

McCarthy’s recommendations

McCarthy’s recommendations are therefore likely to be more difficult to achieve than might appear to be the case. He makes four main suggestions:

First, he suggests establishing “a cross-community coordination and communication body” to align the IG bodies more with one another.

Alongside this, he suggests “an independent action review body”, with more external expertise, to act as a kind of audit body for the internet community.

Third, he’d like other IG entities to assist the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) “in identifying and framing Internet governance gaps”.

And fourth, he’d like to “reform participation structures and create pathways for new potential leaders”.

Concerning which…

Some thoughts on these and then three things I think are missing.

The first and second proposals that he makes seek to address weaknesses in coordination that lead to weaknesses in the way that decisions are made by IG entities themselves. Both make sense but I think both are difficult.

There are powerful vested interests involved within existing IG bodies that would be reluctant to see their influence diminished or diversified. Those include not just those individuals who are wedded to the way things have been done but also commercial businesses that are concerned with maximising the influence they wield.

It’s also hard to see how discussions about a new coordinating body for the internet could avoid becoming arguments about the role of governments and intergovernmental organisations. Discussions about this would be helpful, arguments of the kind that have recurred over the past twenty years less so.

The third and fourth proposals raise questions about the inclusiveness of internet governance arrangements. Participation structures in all international organisations struggle with inclusion and are likely to be dominated by those who have the money, knowledge and resources to be dominant.

Multistakeholderism was meant to be one way of addressing this, but it’s proved hard in many cases to avoid becoming ‘multistakeholderism of the like-minded’, focused round a broad consensus built on past experience. Dominant perspectives make it harder for radical new ideas – like the internet once was itself – to enter into discourse.

Three missing points

The three points that I’d say are missing here, requiring more attention, would be these:

First, responsibility for identifying and framing issues for consideration in internet governance should be much wider.

The IGF, which McCarthy emphasises here, is less technically dominated than other IG bodies, but it’s still primarily a forum of insiders. The biggest gap in internet governance, as he himself identifies, is its focus on technical rather than socio-economic (or, e.g., environmental) aspects/impacts. It’s not internet insiders whose expertise we need most to help identify the gaps in governance but internet outsiders, those who use and are affected by the internet but do not govern it.

Second, the role of governments and international organisations. It’s generally recognised that the ‘wild west’ days of early internet are over and that regulation’s going to be fundamental to IG in future.

Regulation can stop things (which most internet insiders are against) but can also be enabling (by establishing norms for innovation and citizen protections). For some governments regulation is about control but for others it aims at maximising opportunity while mitigating risk. Much of the ethos of the early internet was concerned with minimising government engagement. But no government can afford to ignore the impacts on society arising from the internet. Their engagement’s crucial now to getting regulation right.

Third, the place of traditional IG institutions in the wider IG context.

The entities that primarily concern McCarthy are critical because of their role in the technical management of internet resources. Once they were predominant. Now there is a far wider range of fora and of institutions that address technical aspects of the internet as it intersects with other areas of technology and public policy: that are concerned with what it does as well as how it works. The relationship between these and the internet’s core bodies is increasingly important. At present, it’s ad hoc. It’s too important to be left that way.

Image: Knowledge Café: WSIS+20 via WSIS Process.