Publié le

Dernière mise à jour de cette page le

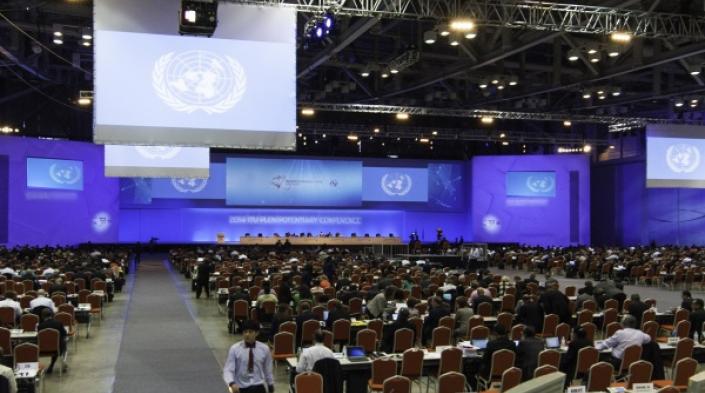

It’s that time of year again. Much like the Olympics, the UN’s International Telecommunication Union (ITU) convenes its plenipotentiary conference where participants compete in feats of strength and endurance, mostly related to staying alert through a marathon of mundane meetings. If any excitement exists (aside from the campaigning for leadership positions), it generally occurs in the run-up to the conference, where U.S. pundits raise the alarm over fears that the “UN is taking over the internet.” Although those concerns are almost always overblown, this year’s event in Dubai will act as a barometer for the geopolitics of internet governance.

A quick refresher on what the ITU does and why its quadrennial plenipotentiary conference, known colloquially as the plenipot, matters. The ITU is a UN specialized agency that manages the allocation of global radio spectrum, develops technical standards for telecommunications, and provides capacity building to member states to improve their access to information and communication technologies (ICT). Every four years, the ITU convenes the plenipot, where member states set the ITU’s strategic direction, finances, leadership, and amend the organization’s constitution and convention as needed.

Beyond the ITU’s core mission of connecting the world, the issues of the day tend to get introduced to the mix. At this year’s plenipot, member states are expected to discuss cybersecurity, the internet of things, digital privacy, surveillance, blockchain, artificial intelligence, over-the-top services and other buzzword-infused topics. How these get addressed, if at all, depends on how member states view the relative importance of the ITU in steering the policy debate on these issues. Many in the developing world look to the ITU for guidance in navigating the public policy challenges associated with new digital technologies. Others, like Russia and a handful of Arab states, look to the ITU to endorse greater control over internet content that would have pernicious effects on human rights.

To the United States and its allies in Western Europe, Canada, and Australia, all of this looks like mission creep. For years now, they have tried to hold the line against an expanded ITU mandate into things like regulating online content. Furthermore, they argue that, as a multilateral institution, the ITU is not equipped to address internet policy issues, as it does not facilitate the meaningful input of stakeholders from the technical community, civil society, and academia. In fact, there are significant barriers to participation, including pretty basic issues around access to information on the proposals to be debated.

This approach has been largely successful so far. The last plenipot in 2014 did not result in any significant expansion of the ITU’s mandate, and even led to changes that made the institution somewhat more transparent and inclusive of non-governmental stakeholders. At last year’s World Telecommunication Development Conference, protracted disagreements on the role of the ITU in cybersecurity resulted in no changes to what had been previously agreed regarding the ITU’s role.

The continued success of their strategy, however, is far from certain. A large swath of the ITU membership expressed deep frustration that no changes were made to a cybersecurity resolution last year despite the pressing cybersecurity concerns they face. That animosity is likely to seep into the plenipot. Furthermore, the failure of two separate UN groups—one on cybersecurity, the other on “enhanced cooperation” with respect to internet policymaking—to issue recommendations could lead states frustrated with the status quo to seek more action from the ITU. These geopolitical cleavages, combined with nationalist sentiment in the United States and elsewhere that hinder international cooperation along with the lack of enthusiasm for alternative multistakeholder forums like the UN Internet Governance Forum, will make it challenging to strike the right balance between addressing some concerns without expanding the ITU’s mandate.

It is too early to predict whether highly controversial issues, like opening up the ITU’s definition of ICTs to include the internet (and therefore bringing a range of policy and regulatory issues into its remit) or organizing another World Conference on International Telecommunication (despite the fact the last one ended in acrimony) will garner serious debate. With any luck, the focus will remain on issues core to the ITU’s mandate, like expanding affordable and reliable access to ICTs in many parts of the world where it is so sorely needed. Either way, the plenipot will surely affect the direction of global internet governance politics in the coming years. Stay tuned.

This blog post was originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations.

Image: Plenary session at the ITU Plenipotentiary Conference 2014 in Busan, South Korea. C. Montesano Casillas/Flickr User ITU Pictures.