Publié le

Dernière mise à jour de cette page le

It’s been a busy month of international meetings around ICTs and internet.

-

The ITU - the International Telecommunication Union – held a Plenipotentiary Conference in Dubai, agreeing its agenda for the next four years.

-

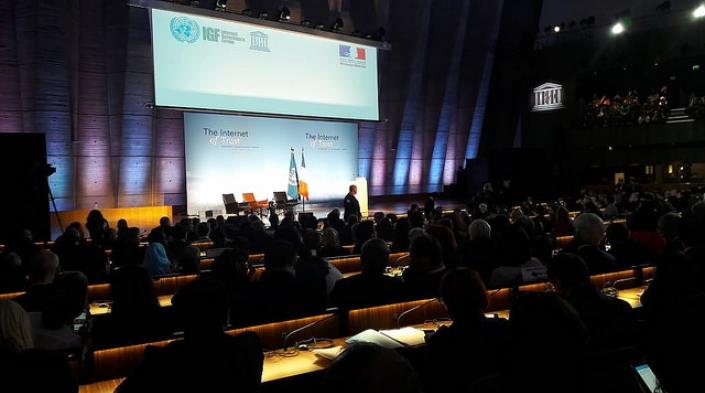

The thirteenth annual Internet Governance Forum (IGF) was held at UNESCO’s conference in Paris.

More on the latter, at least, in a later post.

But another international gathering of significance was held last week at UNESCO. The Council of its International Programme for the Development of Communication (IPDC) approved a new tool for measuring the internet – a set of Internet Universality Indicators which has emerged from eighteen months of research and consultation with all stakeholders.

A bit of full disclosure

Before I go further, I should make full disclosure. The task of developing these indicators for UNESCO was coordinated by APC, with the support of my own organisation ict Development Associates, LIRNEasia and Research ICT Africa. I was lead researcher for the project, with Anri van der Spuy as colleague.

OK. Confession made or trumpet blown. What are these indicators? What are they for and how will they be used? What lessons can be learnt from the experience of their development?

What are the indicators?

The IUIs (as known for short) are a new way of looking at the overall internet environment. They’re intended to help governments and other stakeholders to do three things:

-

to develop a clear and substantive understanding of their national internet environment;

-

to assess that environment in relation to UNESCO’s four ROAM principles (see below);

-

and to develop policy approaches and practical initiatives that will enable them to meet their goals (and the UNESCO principles) as the internet moves forward.

There’s an important distinction here between these and most other UN indices and indicators. The IUIs are NOT intended to compare one country with another, or to establish league tables of performance. They seek to measure internet outcomes in order to improve decisions about what needs to happen, not to offer praise or shame. Using them is voluntary. But using them, it’s hoped, should help governments and other stakeholders to do a better job.

What are the ROAM principles?

The ROAM principles, the basis of these Indicators, are part of UNESCO’s concept of Internet Universality. That concept seeks to maintain aspects which have proved successful in facilitating the internet’s development, to contribute to sustainable development and human rights, and to address the challenges/harms/risks which have emerged within the internet environment.

The ROAM principles envisage an internet that is:

-

built around human rights (R)

-

open (O)

-

accessible to all (A)

-

and nurtured by multistakeholder principles (M).

What’s in the indicators?

The indicator framework that’s on offer here’s substantial.

First, there are five indicator categories – the four ROAM categories and a fifth, cross-cutting, category that’s concerned with gender, children, sustainable development, trust and security, and legal and ethical dimensions of the internet.

Each category’s divided into a number of themes. That concerned with rights, for instance, includes six themes – the overall policy and regulatory framework, freedoms of expression and association, rights to access information and to privacy, and social, economic and cultural rights. That on accessibility has themes on the policy and legal framework and on connectivity, affordability, equitable access, content and language, and capabilities.

Each theme asks a number of questions and each question is associated with one or more indicators – which may be concerned with the existence and performance of institutions, with quantitative data, or with qualitative assessments made by academic and other researchers.

This structure’s based on UNESCO’s established Media Development Indicators (MDIs), which have now been used in more than thirty countries.

Many questions are needed to build up the picture

There are just over 300 indicators suggested in the framework, which is (obviously) a lot. But there are reasons for this.

First, data on ICTs and their impact vary greatly in quantity and quality from place to place. Some countries have a lot, some very little. A wide range of questions helps because it allows researchers to draw on all the evidence that is available in a particular country, to build up a collage of evidence from what is available, and to draw conclusions that have value even where the evidence is relatively scarce.

Second, policy prescriptions should emerge from thorough understanding, not from skimping through with basic stats. These indicators should help researchers build a comprehensive understanding of the Internet environment in which they are deployed.

UNESCO hopes the indicator framework will encourage more data-gathering and more depth and rigour in assessment. But it recognises too that resources may be limited. Around a third of the indicators have been identified as ‘core indicators’ which could be used for shorter research projects. Contextual indicators have also been identified to help researchers make their findings more relevant to national circumstances.

How were the indicators developed?

These indicators were developed through a rigorous and scientific process.

-

Desk research compiling available resources from existing sources – UN and other international agencies, governments, business, academia, civil society and the Internet professional community.

-

Two rounds of consultation, the first on general principles, the second on a first draft of the indicators, with contributions from more than sixty governments and 250 other stakeholders.

-

Over 40 consultation sessions at international conferences.

-

Pre-testing of the indicators’ viability in four countries and piloting in three – Brazil, Thailand and Senegal.

Few UN projects of this kind have been the subject of such widespread consultation. But it’s made sure the indicators focus on real priorities of policymakers on the ground.

And how should they be used?

This indicator framework’s voluntary. No-one’s going to feel compelled to use it. And it can be used in different ways, by different people.

The indicators themselves will need to be interpreted for different contexts. All the evidence that’s gathered will need to be considered critically. The aim should always be to add value to understanding of what’s going on. Uncertainty should be recorded as uncertainty; weaknesses in data and data analysis unveiled; careful and considered thought given to findings and their implications.

UNESCO hopes that research in different countries will be undertaken by multistakeholder teams. I’d emphasise two things. My experience in using the earlier MDIs showed the importance of including team members with different perspectives in the team – not just different specialisms, but different policy preferences and attitudes. And the pre-tests and part-pilots for these indicators demonstrated the importance of government engagement and involvement in both data-gathering and analysis.

Some thoughts on the experience

Finally, some thoughts on the experience of developing these indicators.

First, it’s clear that we need more and better data if we are to understand the internet at national level and develop more appropriate and forward-looking policy approaches. The quantitative data that we have are often poor or out of date. Much more attention’s needed to establishing a satisfactory and timely pool of data.

Second, much of what we need to know about the internet is not susceptible to quantitative measurement. Numbers can tell us only so much. Qualitative assessment is also important, especially in comprehending what’s happening to rights, to development, in cybersecurity. More serious, independent analysis is needed of what’s impossible to count. And researchers should be open to the unexpected.

Third, multistakeholder consultation’s really valuable. These indicators were widely welcomed at UNESCO’s decision-making meeting because they’d been the subject of such widespread consultation. Stakeholders felt they’d been involved and listened to. Developing country governments, in particular, recognised the effort that had been made to make the process more inclusive. Time spent on inclusion more than repays effort.

Fourth, nothing lasts for long where the digital society’s concerned. Snapshot assessments will have value; repeating them in ways that show trends within a country will have more. Some indicators will have longer shelf lives than will others. It will be necessary to revisit this framework in around five years to see what’s no longer so important and what’s become more so.

But, in the meantime, these IUIs add to the range of analytical resources that we have on the internet. As well as being used in many countries, I hope that they’ll be widely read and encourage a wider range of readers to think more about what needs to be measured, how to go about it, and what should happen next.

Image: IGF 2018 plenary session, by Arturo Bregaglio.